This article discusses the third element or the “S” in CASE, which stands for “sharing” and “service.” Up to this point, the ideas of staying “connected” and “autonomous driving” have focused on technological aspects, but this time, we will be looking at the changes that will be brought about by these technologies. Until the end of the last century, technology was an evident means by which human desires were fulfilled. Today, however, the evolution of technology has clearly surpassed the evolution of human society. Technological evolution holds the key to social reforms. However, we should not allow the formation of a unilateral relationship where technology is the master and human society is its slave. Technology is only of value if it is incorporated into society. The question of how technology should be accepted by society remains a valid one. This means that technology and society will continue to be involved in a tug-of-war as they confront each other, and both will continue to shift. A similar situation can be observed today in the case of mobility.

Growing mobility

The total distance traveled by people is expected to continue to increase along with macroeconomic growth. The total distance traveled by people globally by car is said to be roughly 10 trillion miles as of 2015, a figure that is expected to double to 20 trillion miles by 2050. On the other hand, global sales of new vehicles are expected to reach the saturation point of 140 million units per year by 2035-2040 before declining. To “use” something does not necessarily mean to “own” it. In other words, “private ownership” is not an absolute necessity if the purpose is simply to “travel.” Thus, “travel” is increasingly being transformed into a service, creating a “sharing economy” that broadly encompasses public transportation such as trains and buses. The background to this is the evolution of ICT technology, which is a means of solving problems such as the increase in traffic accidents due to a higher traffic volume and aging populations, as well as those associated with urbanization (such as problems with parking spaces in urban areas, the convenience of cities with developed public transportation systems, etc.). Moreover, in other aspects of daily life such as housing and clothing, people are not obsessed with individual ownership and can accept the idea of sharing various items. This is also true for mobility.

Broadly speaking, the “sharing” of mobility can be broken down into two aspects: the “sharing of the means of transportation” and the “sharing of the transportation itself.” With regard to the sharing of cars in the former sense of sharing, examples include long-term car rental as well as options for the shorter term such as short-term rentals and car sharing. On the other hand, the latter sense of sharing includes public transportation such as trains and buses, the taxis that we are familiar with, as well as new options such as ridesharing or ride hailing services which have become popular in recent times.

Sharing of “transportation = mobility”

Uber’s founders Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick came up with the idea of ride hailing after having trouble getting a taxi near the Eiffel Tower when they were visiting Paris. They thought that it would be great if normal cars that were not taxis could pick them up as if they were taxis, an idea which they then put to work in reality using technology. That technology is integrated into an app for smartphones that can be found in ride hailing vehicles. First of all, instead of cruising aimlessly for passengers, the app allows for the detailed matching of available drivers and commuters. Secondly, a safe and efficient route is sent to the driver through the app, making smart commuting possible. Thirdly, the actual route taken by the driver and the driving conditions can be monitored through the app, resulting in more effective labor management. The skills and experience that used to be manually accrued on the job have been replaced by big data that is accumulated in the cloud, which can be systemized and distilled to allow amateur drivers to provide services that are indistinguishable from those of professional taxi drivers.

What is also important is that drivers who are offering the ride hailing service are not formal employees of the ride hailing company. These drivers use their own vehicles and work whenever they wish as ride hailing drivers, receive technology and information provided by the ride hailing company, and share their revenues from passengers with the company. In other words, each driver is in some sense a small business owner who is engaged in a gig economy. This means that countless gig economy drivers are leveraging on the platforms based on big data and AI analysis built by the ride hailing companies. They receive information that has undergone data analysis from the platform and use it to offer ride hailing services to passengers, while simultaneously contributing back to the platform via the information provided during the commute. Passengers who use these ride hailing services will also rate their commuting experience after their ride. These ratings will be used to evaluate the gig economy drivers and will have an impact on their future income.

Commuters are also connected through the Internet, through which they exchange information on their commuting experience. After exchanging information with one another, the apps of ride hailing companies with positive ratings are selected for use by the commuters (consumers). The aggregation of these choices made by commuters forms the brand value of each ride hailing service. As a result of this, commuters will repeatedly use the services of platforms with high brand value. The gig economy drivers, who are the service providers in this system, will also switch to platforms with high brand value. This leads to a snowball effect for the large-scale companies in the industry.

However, it is not only brand value that matters. Indeed, commuters tend to select platforms with high ratings and whose service has a high brand value. However, if the selected platform is unable to promptly dispatch a vehicle, it may not generate any revenue. In order for vehicles to be promptly dispatched, it is necessary to forecast demand in advance using AI based on big data. As a result, the competition between platforms boils down to not only a direct competition of the number of vehicles they own, but also their ability to refine their management of these vehicles.

Furthermore, regardless of the accuracy of the forecasted demand, revenue is not always guaranteed. To generate revenue, it is essential to meet this demand with adequate supply, i.e., to attract gig economy drivers to participate in this dynamic platform and offer their services. These drivers are not limited to offering their services on any single platform. They have access to multiple platforms in order to select the platform that benefits them the most. The key to this system is the concept of dynamic pricing. If the price is too high, consumers will not purchase the service. On the other hand, if it is too low, revenues will decline. There have been concerns regarding the setting of exploitative prices by platforms. However, the “price” may not always reflect the “value” of the service in the mind of users. While the “price” is set before the user uses the service, the “value” is based on the user’s experience after using the service, which will in turn influence the “price” the next time he/she uses the service. In other words, as long as the price is less than the user’s experiential value, it does not constitute “exploitation.”

Relationship with the taxi industry

Needless to say, the rising popularity of ride hailing has greatly affected the traditional taxi industry. In particular, at the height of its proliferation in 2014-2015, in Europe in particular, it was referred to as the “enemy of the taxi industry,” accused of being “destructive,” and was the target of strong resistance.

In the taxi industry, drivers are employed by taxi companies and protected by labor laws, while ride hailing companies regard their drivers as “service providers without formal employment relationships,” and as such they are ineligible for protection under labor laws. As a result, taxi companies are obliged to satisfy minimum wage requirements and offer the relevant social insurance and welfare pensions, which put them at a disadvantage in terms of labor expenses. Furthermore, the vehicles of taxi drivers are assets of the taxi companies, but in the case of ride hailing, the vehicles are privately owned by the drivers and all expenses related to vehicle maintenance are not borne by the ride hailing companies.

Regarding the abovementioned issue of the applicability of labor laws, the UK Employment Tribunal had ruled in 2016 that “Uber drivers are employees of the company.” In September of this year, the Governor of California in the United States signed the AB-5 bill into law, which states that the classification of gig economy workers (not limited to ride hailing drivers) as self-employed contractors must be contingent on their actual working conditions in practice. The taxi industry continues to insist that the ride hailing industry is itself an illegal practice, and the lobbying for legal reform is underway with the aim of forcing ride hailing companies to shoulder the same obligations so that the two industries can compete on an equal footing, thereby minimizing the handicap faced by the taxi industry.

In Japan, taxi companies are regarded as “general passenger automobile transportation business operators” and are required to obtain a business license from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Thus, taxi drivers in these companies are required to obtain a Class 2 license. As a result, barring a few exceptions, there are no ride hailing passenger services in Japan. However, major taxi companies in Japan such as Japan Taxi have plans to develop hailing apps for their respective company groups. At the same time, DiDi has collaborated with existing taxi companies to launch its “taxi-hailing” app in Japan.

The 5 leading ride hailing companies in the world

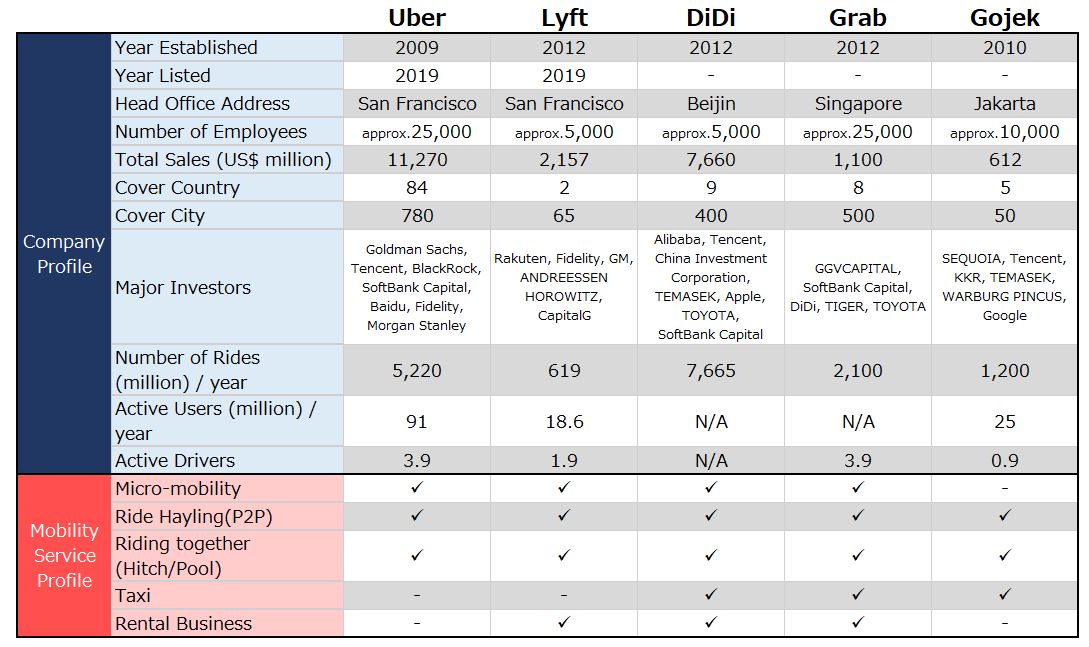

The 5 leading companies in the world for ride hailing platforms are shown in the following table.

Source: Created by SC-ABeam Automotive Consulting Institute based on information published by each company.

Towards the provision of multiple services

As mentioned above, ride hailing services are a form of platform business for whom growth is essential for survival. However, as a passenger transportation business, these services are now increasingly being made to compete with the taxi industry on an equal footing. Indeed, it would be impossible to differentiate oneself from other companies if the focus of these transportation services was to solely offer TaaS (transportation as a service) in the first place.

As such, ride hailing platforms are attempting to differentiate themselves from other platforms and improve the “experiential value” they offer by newly incorporating various other services that go beyond TaaS. Examples of these include:

- “Distribution of goods” in addition to “picking up passengers”: Uber, Grab, and Gojek have started providing food delivery as well as small-lot home delivery and shipping services.

- “Globalization of mobility services”: While Uber is shaping up to become a global platform, DiDi, Grab, and Gojek are also engaged in the regional expansion of their respective platforms in Asia.

- “Acquire travel-related services”: DiDi, Grab, and Gojek have entered the financial and insurance services sector.

- “Implementation of cashless payments”: Grab and Gojek have incorporated a variety of services into an integrated platform and set up a proprietary payment system.

- “Multimodal MaaS initiatives”: Uber and Lyft are laying the groundwork for their participation in multimodal MaaS solutions in the future by having in-house ownership of search engines for bus routes and timetables, as well as avenues for the purchase of passenger tickets.

In these ways, ride hailing platforms are scaling up their operations through the provision of multiple services.

The future of ride hailing and its challenges

Uber and Lyft released their financial statements prior to their listing on the stock market. The revenues reported by both companies for FY2018 according to their released statements are shown below. Both companies had reported significant losses and are expected to remain in the red for some time.

| (Billion dollars) | Total Sales | EBIT |

| Uber | 110 | ▲30 |

| Lyft | 20 | ▲10 |

While autonomous driving may be one solution for these companies to break out of this situation, it would require significant changes to their existing business models. Fully self-driving cars (level 4 and above) cannot be privately owned, and even if they exist, there would be very few of these cars available. Therefore, companies would need to have their own self-driving cars in order to provide this service, and that requires massive investments.

There are also technical challenges with autonomous driving that remain unresolved. In July of this year, GM’s self-driving department “Cruise” announced that it would be delaying the launch of self-driving taxis which was initially scheduled to happen by the end of the year, as the company believes that it would not be possible for the vehicles to demonstrate that they satisfy the required performance and safety standards within this time frame.

Meanwhile, MaaS self-driving cars developed by Bosch were exhibited at IAA 2019, which was held in Frankfurt in September of this year. It is projected that there will be 2.5 million units of such vehicles around the world by 2025.

Nevertheless, as outlined above, in order for us to achieve mobility services as diverse as the forecasting of commuting demand, precise dynamic pricing, autonomous driving, multimodal MaaS, and the provision of multiple services, nothing less than a dramatic improvement in our existing computational capabilities is required. In other words, quantum computers may be the key that will unlock our future.