Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, who took office in September 2020, declared in his first statement of belief after taking office on October 26th, “aiming to realize a carbon-neutral, carbon-free society that will eliminate greenhouse gas emissions as a whole by 2050”. Previously, based on the Paris Agreement, the Government of Japan stated that it would aim to realize a carbon-free society as soon as possible in the latter half of the 21st century, and that it would aim to reduce greenhouse gases by 80% by 2050.1 But in his statement of belief, the government set a goal that went even further.

On December 3rd, NHK published an article entitled “Going ‘gasoline-free’: Aiming for all new cars sold to be ‘electrified vehicles’ by the mid-2030s.”2 The article reported, “The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is building consensus toward setting a goal of eliminating gasoline-only cars from the new-car mix in Japan by the mid-2030s, and having all new cars be hybrid vehicles, electric vehicles, etc.” (underlined by author). With regard to the goal of having new cars sold in the mid-2030s be “electrified vehicles,” as a step toward achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, I got the impression that the goal of “turning new car sales into an” electrified vehicle” in the mid-2030s toward the realization of carbon neutrality in 2050″ is not only achievable, but also eminently reasonable, although there are hurdles.

Furthermore, on December 17th, Akio Toyoda, chairman of the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA), held an online press conference at which he stated that “JAMA will do its very utmost to make a contribution in the government’s plans for carbon neutrality by 2050.” He said that “efforts to achieve carbon neutrality may lead to a loss of industrial competitiveness unless the entire supply chain is involved, and the goal will be difficult to achieve without major changes to the nation’s energy policy,” and he emphasized that “electrified vehicles are not the same thing as electric vehicles.”3

Then in the following week, on December 25th, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) published the “Green Growth Strategy towards 2050 Carbon Neutrality.” The strategy document states that the effort to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 is “an industrial policy for the purpose of creating a virtuous cycle for the economy and the environment.” The document also identifies 14 important fields, sets high goals for each of the fields, and affirms that “the Government will do its utmost to support positive efforts made by the private sector.”4

In particular, in my opinion, the fact that the strategy includes a specific roadmap for achieving decarbonization in the power-generation sector represents a real watershed. Admitting that “it will be difficult to have renewable energy meet 100% of the total demand for electric power” and that “some minimum amount of thermal power will need to be used”, the document plans for the reductions in CO2 emissions to be achieved by 2050 — while simultaneously satisfying increased demand for electric power — by installing as much renewable energy as possible and making maximum use of existing nuclear power plants (which will be made safer) and next-generation reactors, by using “zero-emission thermal power” consisting of green fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen so as to compensate for power fluctuations that renewable energy and nuclear power together have difficulty handling, and through CO2 recovery, and to me it seems that this plan is not only quite feasible but also will involve very little “pain” through drastic changes. METI states that it “will implement this strategy in a steady manner and, in collaboration with related ministries and agencies, hold more concrete discussions on goals and measures toward future revision of the strategy.”

Although electrification is indispensable in order to reduce the amount of CO2 emitted when automobiles are driven, electrification is merely a means for reducing CO2, not an end in itself.

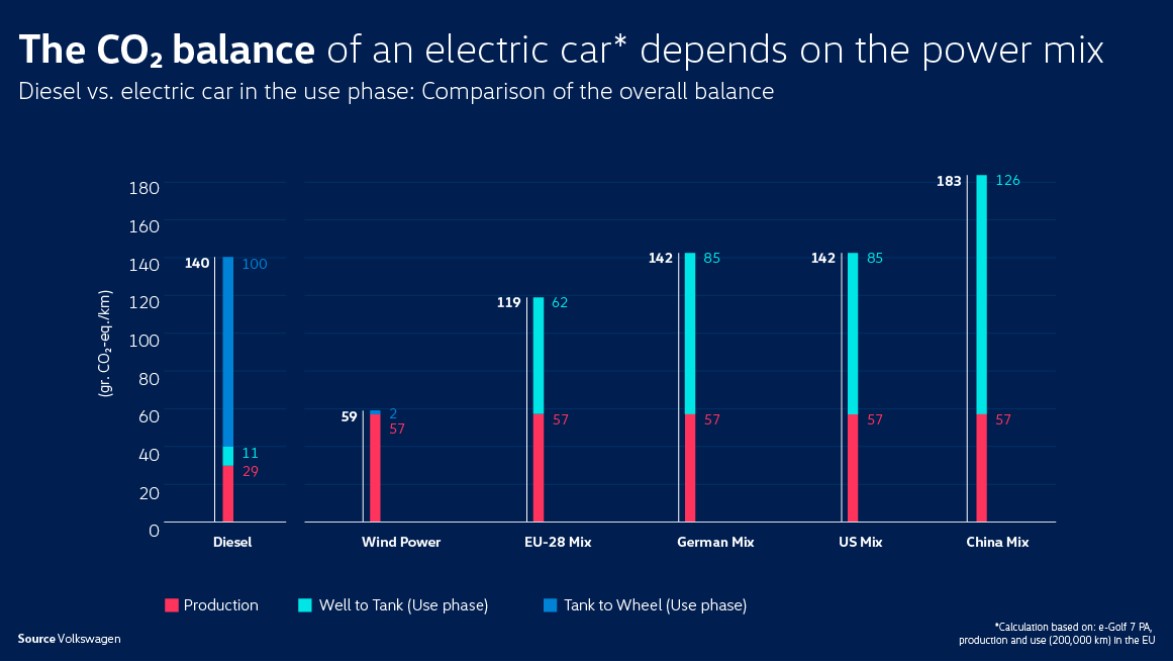

In order to reduce total CO2 emissions, what must be reduced is not just the amount of CO2 emitted while driving (i.e., “Tank-to-Wheel”) but also the CO2 generated when the fuel (electricity in the case of BEVs and PHEVs) is produced and distributed (i.e., “Well-to-Tank”) as well as the CO2 involved when automobiles are manufactured (including the manufacturing of the raw materials) and disposed of (based on a life cycle assessment or “LCA”). Volkswagen has published some interesting data on this subject, and I would like to share it with you.

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the total amount of CO2 emitted by a Volkswagen e-Golf (a battery EV) and a Golf 7 (a diesel-powered car) by the time they have traveled 200,000 kilometers, with the total consisting of emissions from manufacturing the vehicle, emissions from producing the fuel, and emissions from the fuel itself. It turns out that the amount of CO2 emitted by the e-Golf is lowest (naturally) when the car is charged using electricity coming 100% from wind power, but when the e-Golf is charged using the average electricity mix of the 28-country European Union, its CO2 emissions are only a bit lower than those for the diesel Golf 7 (i.e., 119 g per kilometer driven for the e-Golf vs. 140 g for the Golf 7). In Germany, where the share of electricity generated by coal-fired power plants is high, the e-Golf emits more CO2 than the Golf 7, and in China, which has a lot of low-efficiency coal-fired power plants, the e-Golf emits roughly 30% more CO2 than the Golf 7.

Fig. 1. Comparison of the amount of CO2 emitted by a diesel car and the amount emitted by a battery EV using various electricity mixes

Because currently there is no set method for calculating an LCA, people have expressed a variety of opinions with regard to this data. Nevertheless, it would seem that in publishing this data, Volkswagen, which is committing itself to battery EVs in order to erase the stain on its reputation caused by the Dieselgate scandal, is conveying the same message as the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association, i.e., that it will be impossible for automobile manufacturers to meet the CO2 reduction targets on their own, and that there is no way to achieve carbon neutrality unless companies that manufacture parts (including battery materials) and power companies also join in a concerted effort.

Since the Japanese government has now laid out a specific, realistic roadmap for decarbonization of the power-generation sector, automobile manufacturers can now draw up detailed schedules for how to proceed with electrifying their vehicles in order to contribute to minimizing CO2 emissions at the different points in time.

In order for us human beings to live sustainably on Earth, it is essential that we reduce CO2 emissions and achieve carbon neutrality. However, carrying this out forcefully — with the justification that it is “saving the environment of the planet” — by installing solar or wind power so rapidly that renewable energy surcharges (and power bills) rise steeply, or through overly aggressive policies that make electrified cars the only cars on the market before they have become affordable, so that low-income people, and people in developing countries who will want to buy a car in the future, are unable to afford a car, would be to violate two of the Sustainable Development Goals: Goal #1 (“End poverty in all its forms everywhere”) and Goal #10 (“Reduce inequality within and among countries”).

My hope is that the publishing of the “Green Growth Strategy towards 2050 Carbon Neutrality” will serve as an opportunity for discussion regarding the path to be taken in order to achieve painless, truly sustainable carbon neutrality.

1 “Japan’s Long-term Strategy under the Paris Agreement” (Cabinet decision of June 11th, 2019)

2 https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20201203/k10012743081000.html

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjMg8IsWjIQ&t=1914s

4 https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2020/12/20201225012/20201225012.html