Introduction

During the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, lifestyles have seen significant changes due to causes including a long period of self-restraint in going outside. Although the declaration of emergency has been lifted in Japan, the effects of the pandemic continue. This paper examines circumstances surrounding the increasing demand for food delivery services during the pandemic, with reference to relationships to mobility.

The long-term shift to service consumption, and the necessity of external services

Before examining the topic, I would like to survey the background to the increasing need in Japan for outsourcing of household labor, including delivery services, prior to the pandemic.

Consumption behavior in postwar Japan has shifted over a long period of time from mass-production-oriented passive consumption of goods, to individual-led diverse consumption behavior. From as early as the 1970s, following the proliferation and saturation of consumer durables centered on home appliances and automobiles as well as the subsequent two oil crises, a shift is said to have been occurring from uniform consumption of goods to consumption of individualized diverse goods and consumption of services with a focus on experiences.[i]

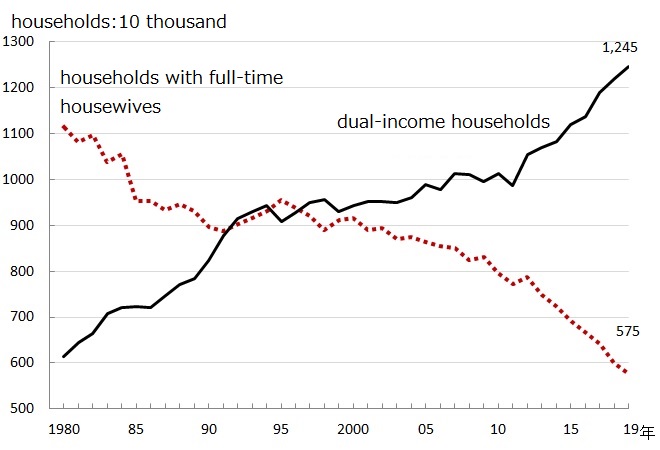

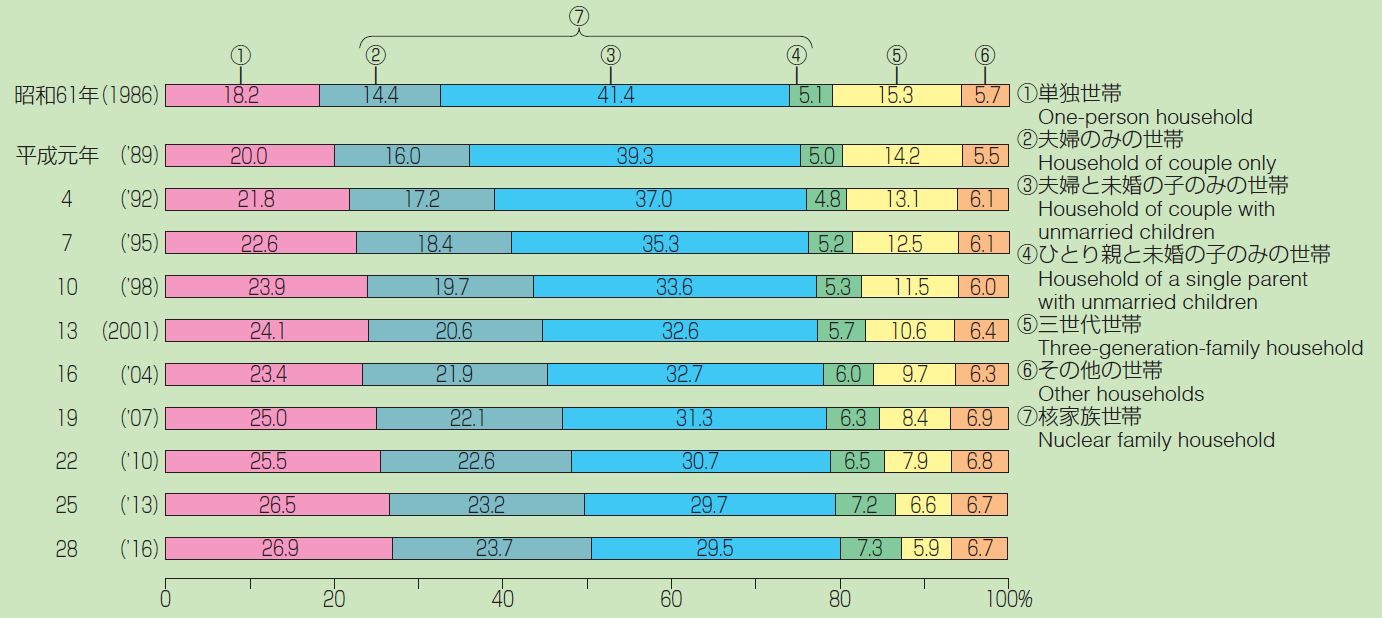

Another element behind the heightened need for service consumption has been changes in the household environment.[ii] In other words, due to the declining birthrate, aging population, the entry of women into the labor market, the increase in dual-income households (Fig. 1)[iii] and the increase in single-person households (Fig. 2)[iv], demand grew for services enabling the outsourcing of housework, childrearing, nursing care, and other domestic work (so-called external services). In particular, double-income households roughly doubled while households with full-time housewives[v] roughly halved between 1980 and 2019, pointing to increasing need for the division and streamlining of domestic work.

Fig. 1: Changes in number of households with full-time housewives and number of dual-income households

Fig. 2: Change in the composition ratio of number of households, by household structure

Moreover, smartphone apps and other recent technological innovations are driving the realization of diverse and tailored external services.

It is thought that, during the pandemic, many people have avoided going out in response to the emergency declaration, requests to suspend business, stay-at-home policies, or simply the personal desire to avoid the risk of infection, resulting in a high number of users of delivery and other external services. I will examine this below.

Home delivery demand under the pandemic

Demand for home delivery grew during the pandemic, due to the need to procure goods, eat, and enjoy entertainment while avoiding going out.

As an example showing the relationship between consumers and delivery services during the period of refraining from going out, a look at the mail order marketplace reveals considerable growth in demand for Amazon and Rakuten home delivery services.

According to Amazon’s quarterly earnings announcement[vi], sales from January to March 2020 increased by 26% year-on-year (a record for the period) to $75.452 billion (approximately 8.9 trillion yen) as demand for online mail order increased[vii] under restrictions on going out during the pandemic. Although a breakdown for the Japanese market has not been released, Amazon Japan President Jasper Chan noted that the use of online mail order during the period of self-restraint increased significantly, with demand greatly exceeding peak demand during normal times.[viii]

At Rakuten, too, shopping e-commerce[ix] increased significantly, with the total for April 2020 up approximately 58% year-on-year (specific amount not announced).[x]

Increasing use of food delivery services, and factors behind the increase

What are the most frequently used categories of delivery services under the self-restraint of the corona pandemic?

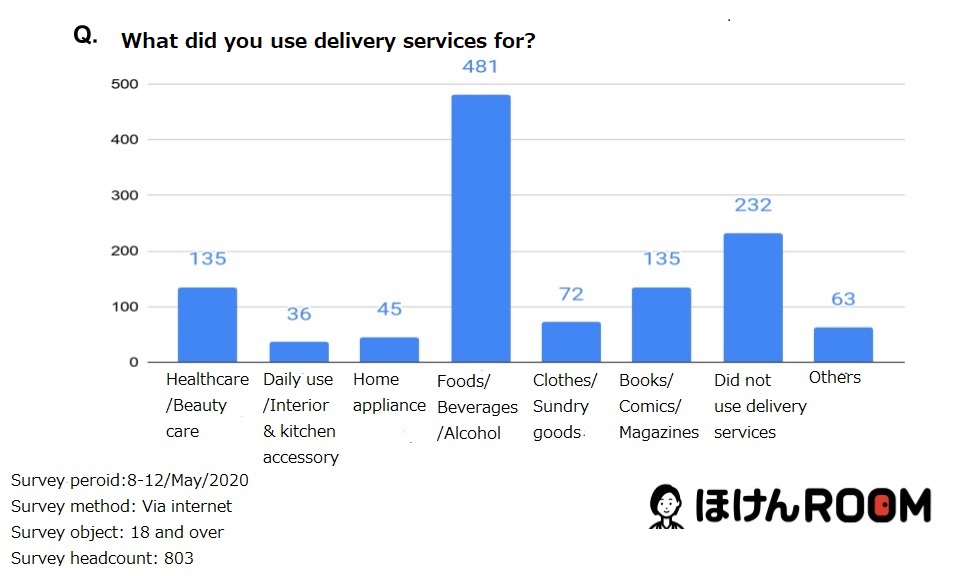

According to a survey[xi] by K.K. Wizleap, which operates the Hoken ROOM online insurance consultation service, users of the “food/beverage/alcohol” category – that is, food delivery users – stood out among delivery service users. (See Fig. 3. About 84% of delivery users use food delivery. May 8-12, 2020. Multiple responses possible. 803 persons surveyed.)

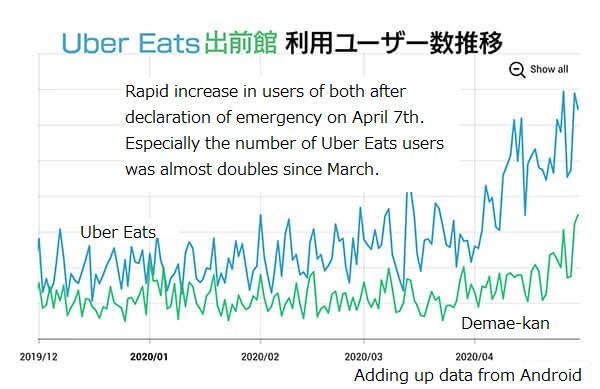

Looking at food delivery conditions from the supply side, the number of users of Uber Eats and Demae-can, two major players, increased sharply since from early April, when the emergency declaration was issued (See Fig. 4. December 2019 to April 2020).[xii]

Fig. 3: Details of services used by delivery service users

Fig. 4: Change in numbers of users of Uber Eats and Demae-can

From this, it can be seen that food delivery services have experienced active use under conditions in which all restaurants refrained from doing business, and people stayed at home to avoid the risk of infection.

Further considering the underlying factors, Eddie Yoon, the founder of US-based think tank EddieWouldGrow, LLC, took up the food business (home cooking, delivery, takeout, etc.) in a recent article in Harvard Business Review[xiii], and named the following three points as factors shaping post-pandemic consumer behavior.

- Increase in work from home: An increasing number of workers are able to indefinitely choose telework, which correlates with time spent cooking (or dining) at home. It is expected that an increasing number of people will work from home in the post-pandemic era.

- Increase in number of single-person households: Generally speaking, cooking for one is inefficient and offers little advantage for a single person. The increase in single-person households was a major factor behind the decline in the cooking population in the United States.

- Increase in the need to avoid crowded environments: Demand for delivery is rising as consumers wish to avoid crowded spaces. Supermarkets and restaurants have been pressed to meet the demand for home delivery.

Although the above considerations concern the US, the same can be said for other countries with a background of increasing work at home and increasing single-person households, including Japan. It is thought that telework, which had been promoted in Japan before the pandemic, will continue to see adoption, and many companies have already announced its adoption as a permanent feature[xiv]. As noted above, the number of single-person households is also increasing in Japan. In addition, with the novel coronavirus spreading worldwide, it is expected that an end to the pandemic will take several years[xv]. Recent reports suggest difficulty in achieving herd immunity, and with no end in sight, it is thought that avoidance of the “3S” dangers will be a prolonged ordeal.[xvi]

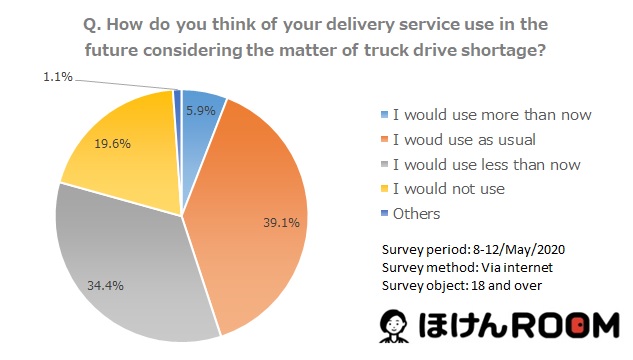

The preceding suggests that the demand for food delivery in Japan is unlikely to disappear, and rather will increase. In the above survey by Wizleap, about 79% of the respondents stated an intent to continue using delivery services in some manner in the future (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Future intent regarding delivery services

Food delivery services and mobility

As delivery services necessarily require means of transportation, they can be seen as having a strong relationship with mobility. In closing, I will discuss the mobility used in food delivery services.

Bicycles and motorbikes are the primary means of transportation used at present by mainstream food delivery services. The means of transportation currently used by Uber Eats are: (1) bicycles, (2) motorbikes, (3) motorcycles (engine displacement 125cc or higher), and (4) light automobiles[xvii]. (For (3) and (4), commercial vehicles, i.e., those with green or black license plates, must be used.) Means of transportation used by Demae-can are nearly identical: bicycles and motorbikes.[xviii]

In addition to the above, there has also been entry into the food delivery industry by the taxi industry. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism has approved a special exemption for the delivery of food and beverages by taxi from April 2020 as a pandemic-related measure. Already, about 1,600 companies and 47,000 vehicles have entered the market. The special exception has been extended through the end of September, and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism is examining permanent status for the measure[xix]. Increased delivery business due to the pandemic will help supplement the passenger transportation business lost to the taxi industry under the pandemic. The structure is similar to the relationship between Uber and Uber Eats.[xx]

In the future, delivery services could become a market in which ultra-compact mobility[xxi] plays an active role. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism is promoting the adoption and proliferation of ultra-compact mobility to achieve ends including CO2 emissions reduction, energy conservation, and efficient use of roads[xxii]. According to workshop materials released by the Ministry[xxiii], the size of the market for ultra-compact mobility (considered to have advantages over existing vehicles) is estimated to be about 11.7 million vehicles on an owned unit base. This number includes about 190,000 collection and delivery vehicles, which in turn includes about 24,000 vehicles related to beverage and food delivery.

In ultra-compact mobility, policy is moving toward categorizing two-seater compact electric automobiles as an official type of light automobile, with market sales promoted from 2020[xxiv]. Yano Research Institute predicts that domestic sales of ultra-compact mobility will be approximately 7,000 vehicles in 2025 and 10,000 vehicles in 2030.[xxv]

At the same time, it has been noted that food delivery services have failed to secure sufficient profitability despite the significant increase in demand during the pandemic. In the US, the Uber Eats business announced year-on-year total transaction volume growth of approximately 52% for the first quarter of 2020.

After deducting costs and other considerations, however, the business’s balance was in the red[xxvi]. Increasing costs of sales promotion and safety equipment, along with growing demands by restaurants for reductions in fees, are said to be causes of the financial deterioration.[xxvii]

Issues concerning the safety of delivery staff are also said to remain. Uber Eats Union, a labor union of Uber Eats delivery staff in Japan, announced the launch of a fact-finding survey, citing the need to verify the appropriateness of compensation from Uber in the event of accidents during delivery.[xxviii]

We believe that medium- to long-term demand for food delivery services will appear in the post-pandemic era. If difficult issues concerning profit structure and delivery staff can be resolved and the business structure can be stabilized, food delivery services may hold the potential to massively impact people’s diverse lifestyles and new mobility. I will focus attention on future movements in this area.

________________________________________

[i] Mayumi Hori, “Transformation of Consumer Society and Transfiguration of Consumer Behavior,” ed. The Institute of Policy and Cultural Studies, Chuo University, “Chuo University The Institute of Policy and Cultural Studies Annual Report” No. 17, 2013, pp.139-142.

[ii] Ibid., p. 141.

[iii] The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, “Long-Term Labor Statistics Seen in Simple Graphs” (https://www.jil.go.jp/kokunai/statistics/timeseries/html/g0212.html), viewed on July 10, 2020. The same viewing date applies to the websites listed below.

[iv] Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Director-General for Policy Planning and Evaluation (Statistics and Information Policy), “Household Status Seen in Graphs,” March 2018, p. 6 (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/20-21 -h28.pdf).

[v] Households with full-time househusbands, and same-sex couple households in which one partner performs full-time housework, should be included in the study but are omitted for reasons of data availability.

[vi] Amazon.com, Inc. 2020 Q1 Earnings Release (https://ir.aboutamazon.com/quarterly-results/default.aspx).

[vii] The Nikkei Online Edition, “US Amazon Sales increase 26%, January-March, Demand Increases under Pandemic,” May 1, 2020 (https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO58688420R00C20A5I00000/).

[viii] The Nikkei Online Edition, “Amazon Japan President Speaks on the Future of Online Shopping,” June 30, 2020 (https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO60928230Z20C20A6EE8000/).

[ix] Shopping e-commerce is the total for Rakuten Ichiba, the B2C business group (fashion, books, Rakuten24 (daily goods mail order), online supermarket, and open EC), and Rakuma (flea market app). Rakuten, Inc. FY2020 Q1 Earnings Results (https://corp.rakuten.co.jp/investors/documents/results/).

[x] Same earnings results as above.

[xi] Shohei Tanikawa ed., “Survey of Awareness of Rapid Growth in Home Delivery/Delivery,” Hoken ROOM Money/Life, May 14, 2020 (https://hoken-room.jp/money-life/8616).

[xii] Mia Itoshiro, “Uber Eats & Demae-can App See Rapid Growth in Use from Declaration of Emergency – Bank and Securities Company Users Also Increase,” Business Journal, May 20, 2020 (https://biz-journal.jp/2020/05 /post_158181.html).

[xiii] Eddie Yoon, “3 Behavioral Trends That Will Reshape Our Post-Covid World,” Harvard Business Review, 26 May 2020 (https://hbr.org/2020/05/3-behavioral-trends-that-will-reshape-our-post-covid-world).

[xiv] As of July 10, 2020: Twitter, Toshiba, Fujitsu, Toyota Motor, etc. Regarding Twitter: CNET Japan, “Twitter Allows Permanent Work from Home for Some Employees,” May 13, 2020 (https://japan.cnet.com/article/35153655/). Regarding Toshiba: Jiji.com News, “Toshiba to Make Work from Home Permanent, Even after Pandemic,” June 5, 2020 (https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2020060501129&g=eco). Regarding Fujitsu: Nippon Television News 24, “Fujitsu: All Employees to Work Remotely,” July 6, 2020 (https://www.news24.jp/articles/2020/07/06/06673253.html). Regarding Toyota Motor Corporation: SankeiBiz. “Toyota Expands Work-at-Home System; Considering Permanent Telework and Application to Factory Work,” July 2, 2020 (https://www.sankeibiz.jp/business/news/200702/bsc2007020500003-n1.htm).

[xv] Ryo Hanamura, Kentaro Tahara, “Scenario for the End of the Pandemic, and for the World Afterward (3) Will It be 3 to 5 Years from Now?,” Nikkei Biotech, April 30, 2020 (https://bio.nikkeibp.co.jp/atcl/news/p1/20/04/24/06847/).

[xvi] Jiji.com News, “COVID-19 Antibodies Decrease in 3 Months: Is Herd Immunity Difficult? – Spain Ministry of Health,” July 7, 2020 (https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2020070700193&g=int).

[xvii] Registration requirements for delivery partners, Uber Technologies Inc. website (https://www.uber.com/a/signup/drive/deliver/).

[xviii] Demae-can delivery crew recruitment, Demae-can website (https://www.demaecan-jobs.com/).

[xix] Jiji.com News, “Consideration of Making Taxi Home Delivery Permanent – COVID-19 Measure, High Need – Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism,” July 8, 2020 (https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2020070700724&g=eco).

[xx] However, it has been pointed out that issues remain for profitability at Uber Eats (see below).

[xxi] The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism defines ultra-compact mobility as “a vehicle accommodating one or two people, is more compact than an automobile and has a tighter turning radius, excels in environmental performance, and is a convenient means of local transport.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Road Transport Bureau, Engineering and Environmental Policy Division, “Achievements and the Future of Ultra-Compact Mobility,” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, “Workshop on Co-Existence of Ultra-Compact Mobility with the Community,” 1st session, Document 1, December 21, 2016, p. 10 (https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001158768.pdf).

[xxii] Ibid., pp. 4-9.

[xxiii] “Ultra-Compact Marketability/Business Feasibility,” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, “Workshop on Co-Existence of Ultra-Compact Mobility with the Community,” 4th session, Document 2, June 21, 2017, p. 4 (https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001190040.pdf).

[xxiv] Yano Research Institute, “Domestic Sales of Next-Generation Mobility (Electric Trikes, Electric Mini-Cars, Ultra-Compact Mobility) to Expand to 8,300 Vehicles in 2025 – Proliferation Expected from 2020 with Establishment of Ultra-Compact Mobility Standards,” Yano Research Institute, Ltd. website, March 12, 2020 (https://www.yano.co.jp/press-release/show/press_id/2387).

[xxv] Same website as above.

[xxvi] Aarian Marshall, “Everyone’s Ordering Delivery, but Apps Aren’t Making Money,” WIRED, 29 May 2020, (https://www.wired.com/story/everyones-ordering-delivery-apps-not-making-money/).

[xxvii] Heather Haddon, Julie Wernau, “Why Food Delivery Services Don’t Make Money Despite Sharp Demand Growth,” The Wall Street Journal Japanese Edition, May 14, 2020 (https://jp.wsj.com/articles/SB12076302647651404700904586382963218056764).

[xxviii] Yahoo! Japan News, “Uber Eats Labor Union Holds Press Conference; Accident Investigation (Full Text 1) to Validate Injury Compensation System,” January 7, 2020 (https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/e9448e1e96d24e7e6c2e0ac47a6599d4266b7314).